Men at Arms

As the “mancession” continues to displace the traditional male breadwinner and prolong young mens’ extended adolescence, the state of American manliness is much in debate. A clash between two titans of classical liberalism points the way toward the masculine ideal that deserves to make a comeback.

Men at Arms: Rousseau and Burke Debate Masculinity and the Liberal Order

by Adam Nicholson

Kay Hymowitz is worried about unmanly men. The author of Manning Up: How the Rise of Women Has Turned Men into Boys and a series of essays on the “New Girl Order” (the most recent of which appeared at Cato Unbound), she has spilled much ink on her subject: the extended adolescent who delays the traditional markers of masculine development, namely, financial stability, career focus, marriage and children. Hymowitz blames a series of cultural and economic phenomena for the contemporary American male’s failure to launch. These phenomena are closely attached to certain expectations promised by variations of the liberal project.

Before diving in, it is worth noting that the concern with unmanly men is not limited to the realm of intellectuals. Consider that many television shows have a near-obsession with the question of masculinity in the context of the liberal order. Satires like Family Guy mock the traditional family man in an ongoing joke about his failure to live up to norms of traditional masculine responsibility. Crime dramas like The Sopranos and The Wire suggest that masculinity is dangerous and perhaps inherently violent—and in the criminal underworld absolutely necessary for survival. Sitcoms such as Always Sunny in Philadelphia and Two and Half Men draw their humor from the disappointment of men who look for masculine fulfillment while avoiding masculine challenges. Pop culture may not have a clue what true masculinity is, but it certainly taps into the abiding relevance of today’s critique of men and the conflicts it poses with liberal assumptions about justice, equality, freedom, government and gender relations.

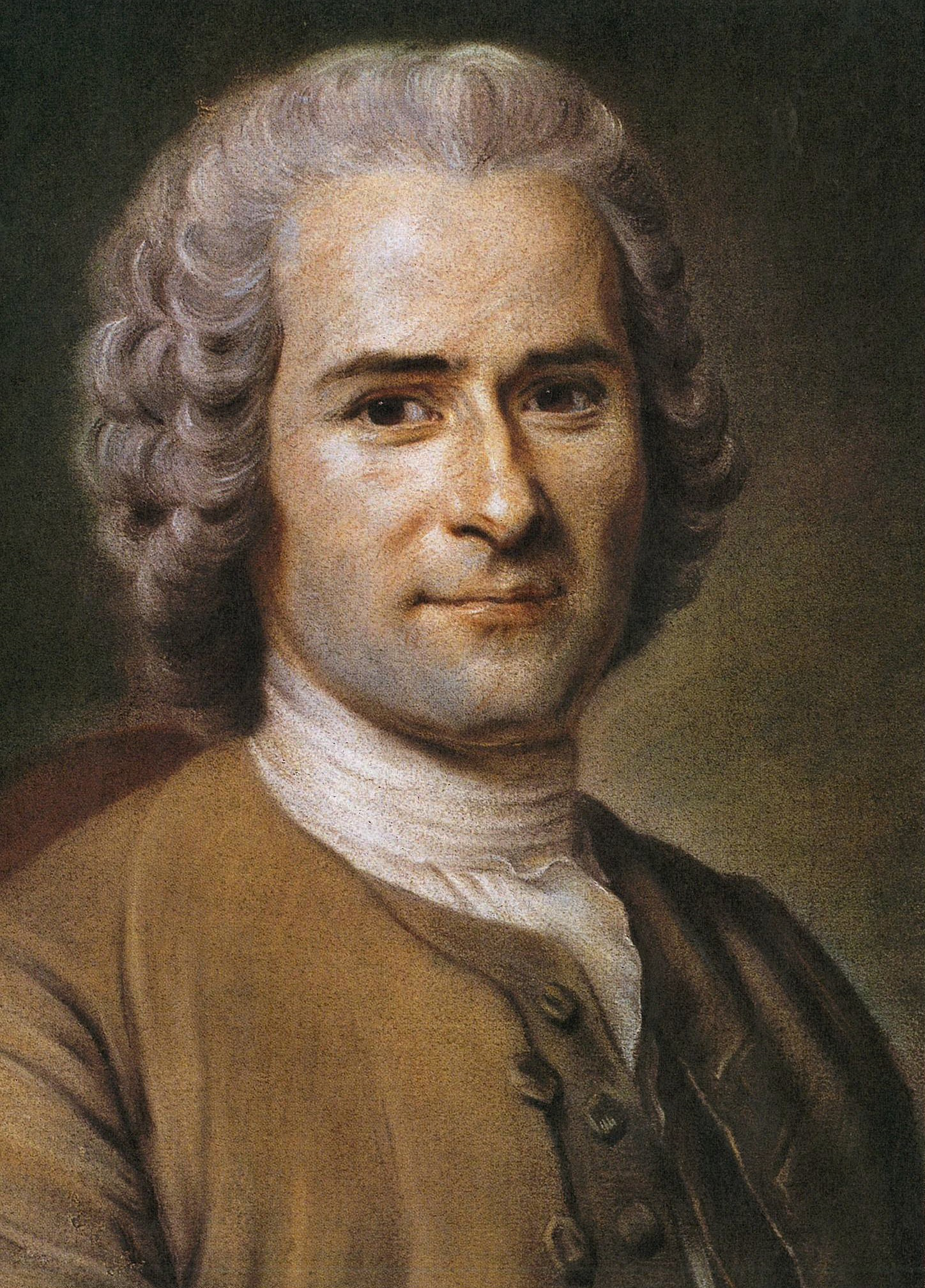

Given that the problem of masculinity has antecedents in liberal thought, let’s turn there to attempt to sort out these questions. Fortunately, two formative liberal thinkers, Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Edmund Burke, have already done the philosophical spadework. Rousseau and Burke discussed rival understandings of masculinity within the context of their respective observations on human nature, the role of government, and realm of liberty. By understanding how the definition of masculinity informs their respective philosophies, it is possible to see why masculinity has been so misunderstood and why, more important, a properly-formed masculinity is crucial for the maintenance of the liberal order.

In typical male fashion, I’m making some rather bold assumptions. The first assumption is that masculinity exists. Boys have been, and always will be, boys. The meaningful question is whether they will grow into men, the kind of men that lead well-functioning lives. The second assumption is that the liberal project is a major accomplishment in human development, but requires a philosophical-moral core, a core built or eroded by the men and women who live in a given community.

What does properly formed masculinity look like? To dig deeply into Rousseau and Burke’s understanding of masculinity it is necessary to become familiar with their core understandings of human nature, which find expression in their discussion of “the will.” The will is an element of human nature belonging to both sexes, but one which Rousseau and Burke understood as manifested differently in each. Considering the will’s masculine component doesn’t exclude the value of the feminine counterpart. Rather, understanding the masculine will draws attention its manifestation in men (just as understanding the feminine will draws attention to its manifestation in women).

Rousseau’s understanding of masculinity finds its most succinct expression in Émile: or, On Education, his pedagogical novel. Émile’s namesake character is a young boy whose tutor has developed a method for forming him into the ideal citizen, while enabling him to retain his innate goodness. It is in Émile that Rousseau demarcates the sexes solely according to their purported assertive tendencies: Men “ought to be active and strong,” women are to be “passive and weak”; men “must necessarily will and be able,” while women “put up little resistance.” It is on this basis that Émile is raised to be a strong husband for his future wife, Sophie. Rousseau’s understanding of strength is rather brutish, as we soon learn: In in the sequel (spoiler alert!), Émile and Sophie, Émile decides to leave Sophie when he realizes that his marital vows and other domestic ties are but “chains” that his heart has “forged for itself.”

These passages do not portray mere alpha-male chauvinism (though that arguably is entailed), but rather a window into Émile’s large understanding of the will.” Will, broadly speaking, is the source of human agency; it is what directs an individual toward or away from that which is identified as good. According to Rousseau, “man is naturally good” and the will is the unimpeded, spontaneous impulse in its direction. In his words, “all the evil I ever did in my life was the result of reflection; and the little good I have been able to do was the result of impulse.” Given that reflection is bad, the will must resist any “artificial faculties” (even, for instance, table manners) that might keep man from enjoying his natural freedom and living “authentically” according to his appetite. Rousseau’s concept of the will admits no complexity in human nature, no need to order desires, discipline the mind, or resist temptation. It simply suffices that man follow his inclinations and “all his needs are satisfied.”

Satisfying man’s needs, as has been seen with Émile, is not a political enterprise. In the state of nature, man is satisfied with the “independent intercourse” of ruggedly meeting his own needs and avoiding the corrupting influence of other people. Rousseau admits that politics is a good innovation, but only insofar as it brings new opportunities for man to develop his autonomy. Contrary to Aristotle, who thought the fullest expression of our humanity culminates in the public sphere, for Rousseau man is not by nature a political animal. He has no rational desire to participate in political society (in fact, “reason . . . engenders egocentrism”). Hence, when Émile is ready to become a man and enter political society, he must develop sentiment (or pity), which softens his natural “hard” features and allows him to grin and bear the misery of human company. This pity, of course, was not strong enough to keep him from leaving his wife. Émile “became truly a man” when he “ceased to be a citizen.” He achieves masculinity in the renunciation of his relationality.

The development of Rousseau’s version of masculinity can be seen in the meatheads of modern sports, business, and politics—the men who are too strong for the confines of civilizing life and its obligations. Former governor and actor Arnold Schwarzenegger might be the epitome of masculinity under this model, as revealed by the news that he fathered a “love child” with a member of his household staff. He was simply too willfully independent to be held captive by the bonds of marriage to Maria Shriver. In the media his philandering earned the scolding one typically reserves for young children and the mentally handicapped: He couldn’t help it.

It is for the sake of retaining one’s absolute “freedom” while enjoying protection from the vicissitudes of human nature that man enters political society. In The Social Contract, Rousseau describes the “fundamental problem of politics” as “finding a form of association which defends and protects with all common forces the person and goods of each associate, and by means of which each one, while uniting with all, nevertheless obeys only himself and remains free as before.” Rousseau’s dream is to enjoy maximum autonomy while still enjoying a regular meal, a roof over his head, and safety from those who might harm him or steal his property. In the words of Robert Nisbet, he wants to be liberated from the “toils of society,” from having to exercise the personal responsibility that keeps families intact, communities safe, and governments honest.

Rousseau recognizes that his utopian dream requires elaborate justification. In order to allow everyone to “obey only himself” while retaining the “common forces” of government, Rousseau conceives of the “General Will.” The General Will is an abstraction to describe how the people’s unimpeded, spontaneous will can be channeled into political power. The General Will is what all the people desire when they are acting in accordance with their most natural, personal desires. In the words of political theorist Claes Ryn, the General Will gives “maximum freedom and power to the momentary majorities of the people by placing no strongly resistant obstacles in the way of emerging popular wishes. . . . It elevates the spontaneous impulse of citizens, realized through the majority of the moment.” It celebrates the lowest common denominator of civic engagement.

Moreover, the General Will rests on a very narrow conception of freedom. While it technically enables all citizens to remain “free,” this freedom comes at the cost of their capacity to reflect, question, and form associations outside of the General Will. The General Will chafes at debate, local associations, and any civic action that takes place outside of the General Will. It ultimately posits the state as the “sum of common happiness.”

What started as a project to free citizens from one another, then, ends up making them the wards of the state. Of course, this was Rousseau’s goal all along, as his understanding of individual freedom never entailed the personal responsibility that liberty from state control requires. Rather, his “freedom” is the freedom from work, particularly work of the moral and ethical variety—what he terms the “toils of society.” The masculine man plays a central role because he has the greater capacity to “be active and strong” and resist capitulating to social obligations.

In contrast to Rousseau’s conception of masculinity as assertion of one’s spontaneous will, Burke’s masculinity is conceived as a check on the will. In Reflections on the Revolution in France he argues that the Jacobins’ open-ended assertion of liberty and the rights of man were dangerous and naïve, and posits in its place a “manly, moral, regulated liberty.” Elsewhere he uses the adjective “masculine” to describe members of society who resist dangerous inclinations, both in themselves and society at large.

Like Rousseau, Burke has a theory of the will at work in his conception of masculinity. Burke conceives of the will in a dualistic sense containing both a lower, “first” or impulsive nature, and a higher, “second” or cultivated nature. The will often is driven by the “first nature” to fulfill one’s immediate desires (which may or may not be rightly ordered). In order to serve a good end, the will must be bridled by a “second nature.” When man develops his higher, second nature, he is following the will’s direction towards objective truth. This often entails responsibilities, including responsibilities to other individuals and society in general. According to Burke, humans are inherently relational, inhabiting “a society of the living, the dead, and the yet to be born.” The result of humanity’s natural sociability is that “[w]e have obligations to mankind at large, which are not in consequence of any special voluntary pact.” Burke scholar Bruce Frohnen explains that for Burke, “the virtuous man is the man of public affection, the man who serves society because it is his society, familiar and so loved.”

The manifestation of Burke’s “man of public affection” is the gentleman, who is essential for society:

“Nothing is more certain than that our manners, our civilization, and all the good things which are connected with manners and with civilization have, in this European world of ours, depended for ages upon two principles and were, indeed, the result of both combined: I mean the spirit of a gentleman and the spirit of religion.”

Burke’s gentleman behaves according to the dictates of chivalry, a code that extends beyond etiquette to describe the man’s activity in both private and public affairs. Burke himself appealed to a chivalric ideal in defense of his performance as a Member of Parliament, writing: “I had no arts but manly arts. On them I have stood, and please God . . . to the last gasp I will stand.” In similar manner, Burke describes a colleague, Lord Grenville, who “stands forth, with a manliness and resolution worthy of himself and of his cause, for the preservation of the person and government of our sovereign, and therein for the security of the laws, the liberties, the morals, and the lives of his people.”

It is on the grounds of this chivalric masculinity that Burke criticizes the French in his famous description of the assault of Marie Antoinette. When no one rescues the queen, Burke expresses his sadness that France is apparently no longer “a nation of men of honour. . . . I thought ten thousand swords must have leaped from their scabbards to avenge even a look that threatened her with insult. But the age of chivalry is gone, and the glory of Europe is extinguished forever.” It can be seen that while Burkean masculinity entails assertiveness (and at times the violent assertiveness of the drawn sword), it is always an assertiveness in service of a higher good. Instead of using his thumos to ensure that “his needs are satisfied,” he puts it in the service of “the laws, the liberties, the morals, and the lives of his people.”

This notion of masculinity as disciplined assertiveness retains cachet today, even if it seems more obscure. Consider, for instance, how war heroes are celebrated not for merely vanquishing the enemy, but for placing themselves at increased risk to advance the mission and protect their comrades. Aggression is expected; but it is the soldier’s aggression in service to a noble cause that is rewarded. Similarly, note that despite declinist hysteria over the “hook-up culture” and the prevalent claims that chivalry is dead, many men continue to bow to the conventions of courtship. And women continue to reward it. While men will always pursue, it is regarded one of western civilization’s accomplishments that sexual pursuit is channeled toward protection of women and children. That accomplishment may be threatened today but is far from extinct.

Thus Burke affirms “Liberty connected with order; that not only exists along with order and virtue, but which cannot exist at all without them.” The security of liberty, then, lies not with the General Will but with the representative, the “philosopher in action.” Unlike the General Will, the representative does not respond to the immediate impulses of the people. Nor is the representative averse to reason and reflection. Burke writes that the representative is responsible “to find out proper means towards those ends [of government], and to employ them with effect.” The representative is obligated to understand policy and make prudential judgments in order to advance the common good, which Burke understands as concrete rather than abstract.

A state based on Burke’s understanding of ordered liberty entails a well-functioning civil society and government that checks the excesses of human impulse. It allows maximum possible liberty while impeding those whose moral development does not provide sufficient self-restraint. Burke explains in a letter to a French correspondent that “the liberty I mean is a social freedom,” one that must be combined “with government, with public force; with the discipline and obedience of armies; with the collection of an effective and well-distributed revenue; with peace and order; with civil and social manners. All these (in their way) are good things too and without them, liberty is not a benefit whilst it lasts, and is not likely to continue long.” Good government and a healthy culture (namely, “civil and social manners”) are integral to the enjoyment of liberty.

Burke’s argument for a “manly” liberty now becomes clear. With his understanding that masculinity should entail a check on man’s lower nature, it was only a short extension for Burke to employ the masculinity of the representative in defense of ordered liberty. Burke understood masculinity as an indelible feature of human nature, which when properly developed becomes the force that says “no”—both to individual impulses and to impulse-driven movements. This is not to say that only men should check their impulses. Rather, Burke evinces an understanding that a man’s pursuit of virtue cannot be abstracted from his lived-out masculinity, anymore than a woman’s pursuit of virtue can be abstracted from her femininity. Hence, he appeals to the masculinity of his readers as a means for reaching virtues that transcend their gender.

Rousseau, by contrast, articulated a raw masculinity, one which justified assertiveness in the pursuit of his immediate impulses. Rousseau’s man is simply the more brutish of the sexes when it comes to fulfilling his will and ensuring “all his needs are satisfied.” When Rousseau’s masculinity informs society, it becomes a force behind radical individualism, the General Will, and a “freedom” that one must be forced to accept as dictated by state authority. Rousseau’s masculinity inherently undermines the characteristics of stable, free societies. Further, Rousseau’s masculinity, understood in opposition to femininity, makes no case for respecting women or their contributions as complementary equals, as they are merely the weaker sex. Rather than pointing men towards virtue through their masculinity, Rousseau drives man towards the most basic elements of his nature.

The recent dust-up over Dan Savage’s proposal of “monogamish” marriage, which touts the supposed virtues of negotiated infidelity, warrants comment if only because it shows how easily a simplistic masculinity can be unwittingly co-opted for illiberal ends. When Savage claims that spouses (and let’s be clear, he means wives) should be more accommodating of infidelities because marriage is “difficult” and sexual gratification is of paramount importance, he brushes aside the possibility that this difficulty is in fact part of what makes marriage exciting. “Marriage,” according to G.K. Chesterton, “is a duel to the death which no man of honor should decline.” Marriage is not for those who want the easy route; it is the calling, possibly even the vocation, of the adventurer.

Alexis de Tocqueville observed that the American democratic experiment offers unheard-of freedom for human exploration, development, and achievement. Yet the granting of this freedom was always understood to entail certain corresponding duties and virtues: fulfillment of contracts, willingness to endure hardship, honesty, a solid work ethic, and respect for human dignity, to name a few. To divorce freedom from duty deprives the project of not merely its justice, but more importantly, its adventure. Where there is no risk, there can be no reward.

Savage’s theory doesn’t appeal to the masculinity of his audience, but, ironically, to their impotence. It is a softball for the guys who have seen the work required of civilization-building and decided to sit it out. What he offers is a ticket to free ride on a system that was built by men and which in the long run will fail for lack of men (simply on account of declining birthrates, if not declining ethical self-discipline). The liberal project will have these boys whether it likes it or not. Fortunately, it is not without resources for forming them into men.

Adam Nicholson is a luckless fly-fisher and out-of-shape alpinist who enjoys reading political theory and practicing political hackery.