Deconstructing Globalization

Michael Brendan Dougherty makes an enjoyable @TAC upon the metric system, Hegelianism, and their latest champion, Fareed Zakaria.

The enthusiasts for the metric system (which is based on incorrect calculations anyway) remind me of the enthusiasts for Esperanto. George Soros speaks Esperanto.

But Zakaria’s conclusion is even worse:

Generations from now, when historians write about these times, they might note that by the turn of the 21st century, the United States had succeeded in its great, historical mission—globalizing the world. We don’t want them to write that along the way, we forgot to globalize ourselves.

There is a lot to get into here. First, the surest way of making sure that “generations from now” people will laugh at you is to declare what the history books of the future will say. Second, exactly when did the United States get a great, historical mission? Was this something the Pilgrims came up with? George Washington? Henry Clay? Jimmy Carter even? I find the whole idea that our nation has a purpose chilling. Exactly who and what is going to be mobilized to achieve this purpose? Third, what does globalizing the world even mean? I’m sure it has something to do with free-trade, managed capitalism, social safety nets. But in reality “globalize” is a nonsense verb. Seventy years ago, he would have said we need to “proletarianize” the globe. For Zakaria, “globalization” is a word that in one context has a discreet meaning related to policymaking, but in this context has another purpose: to tell the readers that the future belongs to people who think like him, and that ruin will come to those who stand in the way.

This all sounds about right to me, but the drum I want to beat is a little different. The United States has already succeeded in globalizing the world — by globalizing American culture. What Zakaria wants, I think, is for the United States to succeed at the new task of globalizing itself. Which wouldn’t bother me so much if the fans of globalizing America didn’t have such a troubling obsession with restructuring American labor in shape and substance. Not a single proponent of globalizing America is against maximizing migrant labor among the lower classes and maximizing math and science among the upper classes. My distaste for migrant labor and the hegemony of engineers, each taken separately, is already almost incalculable because of my judgments about what ruins a healthy republic. Taken together, these two great prescriptions for globalizing America fill me with something I must quickly laugh off as paranoid rage.

Everywhere I turn some bold-faced name is guzzling this kool-aid. I never tire of linking to this NYT blog post in which my criticism of Bush’s State of the Union appeal for more math and science education is called “perhaps the most unusual” conservative attack on that speech. On balance, I’m content for America to continue in its capacity as globalizer. I’m much less sanguine about America becoming a globalizee. This isn’t just because I’m a nationalist; it’s because I’m convinced that the United States has, and depends upon, a globally unique system of government which is itself dependent upon America’s unique geopolitical, cultural, and religious heritage. The maintenance of that heritage demands a conscious effort not to regularize the American workforce into a system of migrant drones at the bottom and civil engineers at the top, two types of people with an affirmative interest in destroying citizenship and unmaking the American character.

I’m also convinced, incidentally, that globalizing America will make it much harder for America to globalize itself, because the less America is like what it is, the more impossible, inane, nonsensical, and undesirable it will be for the world to learn from what America got right. Probably the most grievous error of the pro-globalization crowd is its intransigent comprehensiveness fetish: globalizing America hasn’t meant making foreign countries ‘more like the US’ in some kind of holistic, across-the-board fashion; it’s meant exporting the things about America that work, that can travel, that are fungible and useful and beneficial in different cultural contexts. (Yes, this is an incomplete and too-happy picture of what’s happened. But I’m identifying the good so I can contrast it better with the bad.) Globalization, in its natural, uncontrolled diversity, will be and should be an irregular process in which countries pragmatically adopt and appropriate a la carte things from elsewhere that work for them. Globalization as Zakaria and his ilk seem to want it, and want it specifically in America, is a rigorously regularized process in which all countries, like it or not, are compressed toward some kind of hyperlaborious, hypertransient norm of uniformity. I respectfully dissent.

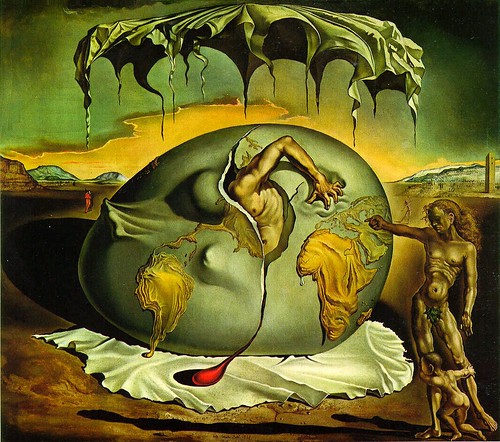

(Dali’s “Geopoliticus Child Watching the Birth of the New Man” courtesy of Flickr user oddsock.)